The idea that “necessity is the mother of invention” is said to date back to Plato’s Republic (~380 BC). While it is a historical fact that inventions are sometimes conceived under circumstances of true need and desperation,

it’s also worth considering that necessity isn't the only parent in the room. For example, the airplane, the automobile, and the telephone were never life-or-death necessities before they were invented. These few examples clearly demonstrate that premeditated want or desire can equally inspire innovation, especially given the fact that most inventions must be nurtured with time and resources, which is contrary to the conditions of duress and scarcity of resources which usually define a condition of absolute need.

Of course, the needs or wants that inspire invention aren't always exactly scripted. In fact, many great innovations (like Post-it notes and Velcro) are prompted by incidental circumstance or unforeseen opportunity. While discovery, like innovation, may be achieved based upon deliberate planning, perseverance, and observation, in most cases, discovery—which often leads to invention—is often a matter of fate or happenstance.

“I returned, and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time

and chance happeneth to them all."

~ Ecclesiastes 9:11 ~

To credit fate with discovery, of course, is not to say that the destiny of individuals or of humanity is materially predetermined or dictated by random chance (which has no causal power), but rather to acknowledge that human destinies are often governed by circumstances outside of our control. In the words of Albert Einstein, “Almighty God does not play dice.”

"The king's heart

is in the hand of the LORD,

as the rivers of water:

he turneth it whither

soever he will."

~ Proverbs 21:1 ~

I believe that man has been granted freewill, and that God is omniscient, omnipresent, omnipotent, personal, and benevolent; and therefore I believe that the fate of individuals and humanity as a whole is a mysterious and precarious mixture of divine providence and human decision. In other words, I believe that God is not an absentee landlord, involving himself in human affairs. And given these principles, I am compelled to say that this Tabernacle discovery is not to be mistaken for a modern Tabernacle invention. Although I am an engineer, I did not set out with a need or even a desire to invent, or reinvent, the ancient Tabernacle of 3,500 years ago. To the contrary, the Project 314 Tabernacle design was the outworking of a discovery and fateful event that was made possible by my favorable response to a divine prompting back in 2014.

Over the course of my life, I have made a point to read the Bible end-to-end, including the Exodus Tabernacle account, on more than one occasion. However, I must confess that I never really made a point to diligently study the Exodus Tabernacle. Truth be told, I was probably more fixated upon the completion of Exodus over the understanding of the content as as I flipped through the pages; but I suppose that my reason for never taking the account very seriously might be comparable to that of millions of other people. After all, it seems boring, outdated, and meaningless at first glance. The pictures and illustration don’t exactly help, as the Tabernacle is usually isn't depicted as something that is innovative or inspirational, or, for that matter, even normal.

Given my admitted levels of indifference, it would be a gross exaggeration to say that my discovery of the ancient Pi constant was as a result of intensive study or subject matter interest. Truth be known, my study of the

Tabernacle really began with an unrelated independent Hebrew etymology study—which was marginally related to the Tabernacle in the first place.

Nevertheless, as I began to peripherally survey the traditional

models of the Exodus tabernacle, some things just didn’t add up. For example, I wondered why the Tabernacle models (like the full size model built in Timna, Israel, as shown in pictures) would feature a flexible leather

rooftop with almost no pitch for watershed.

Furthermore, I started to wonder why people in such a hot climate would build a tent that was covered with four layers of material. Not only did I wonder this as an engineer, but I wondered this as an experienced camper,

having never seen nor heard of a four-layer roof tent, which is exactly how most Tabernacle models are depicted, as shown in the model (1) below.

Wondering how the tent roof layers related to one another, I scoured

the internet—along with the original Exodus account—only to find a collection of inconsistent opinions. Eventually, I came to conclude that the tent did not feature a four-layer roof, as is typically assumed.

But more importantly, my random curiosity and search led me to study the measurements of the sheets used for the tabernacle coverings. While the study of the textile design of a 3,000 year old tent may not sound remotely intriguing at first (or even relevant), I can assure you that there is more to the Exodus account than meets the eye. In fact, after scrutinizing every letter of the Hebrew Exodus text, it started to read like a good word puzzle or one of those clever story problems that you are assigned in math class. Actually, as I began to probe the Exodus text details, I began to see the Exodus text as being written in a way that is comparable to an engineering specification written by a clever and meticulous customer, who was trying to accomplish—and maybe even conceal—an unspoken agenda.

Driven by a combination of frustration and curiosity, I sat down with the Hebrew Exodus account, put my "engineering hat" on, and followed the advice of my father—who was an engineer and professor. Diligently following

Dad’s advice, I made an "FBD with TLC"; which, in his vocabulary, meant that I drew a “Free Body Diagram with Tender Loving Care”. Just like I had done so many times in school and as an engineer, I drew a simplified sketch of what the text described—and only what the text described—without adding assumptions of my own, taking creative latitude with the descriptions, or deferring to traditions. Knowing that I might be in

for a long night, I sharpened my pencil, started drawing curtains, and with a watchful eye, kept a careful inventory of every single letter—and number—in the Exodus Hebrew texts.

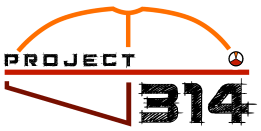

According to the Exodus account, the

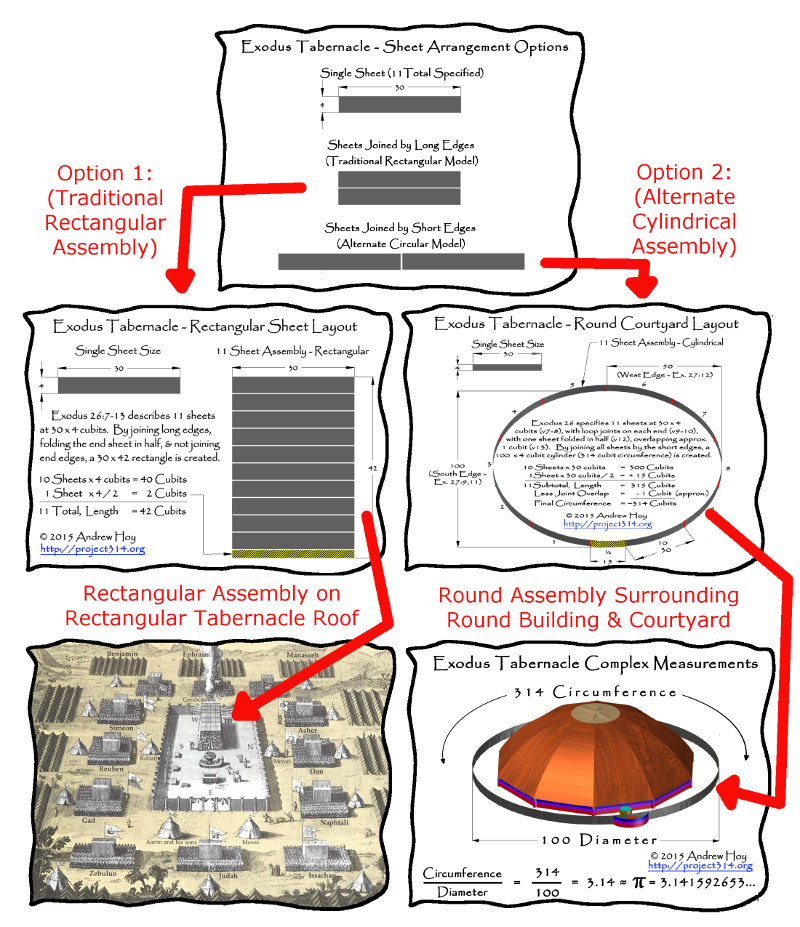

Israelites were to weave 11 fabric sheets (depicted in the image below), each measuring 4 by 30 cubits (which is around 6-8 feet wide and 45-60 feet in length, depending upon assumed cubit conversion standards), complete with loops on opposite edges.

Using the fabric loops in the edges, the craftsmen were instructed to unite all sheets together into a single assembly, at which point they were also told to fold the 11th sheet back over upon itself. It is traditionally

assumed that these curtains are joined together in a top-to-bottom arrangement (i.e., long edge-to-long edge), in order to make a single flat plane sheet measuring 42 x 30 cubits.

However popular this traditional long-edge-to=long edge rectangular fabric swatch assembly approach may be within religious commentaries and artwork, the assumed fabrication method nevertheless fails to comply with the exact Exodus specifications. In particular, it fails to account for two unjoined edges on opposite ends of the assembly, whereas the Exodus text describes all sheets as having loop joints on both edges. Regardless, by means of assumption, a rectangular assembly is created while end sheet edges are left unconnected (depicted in the image above via curtain 1 and the half-sized 11th black-and-yellow curtain above). Nevertheless, given this universal assumption, at this point it becomes very difficult—if not impossible—for students and scholars to perceive anything but a rectangular building, such as the physical models depicted in photos above.

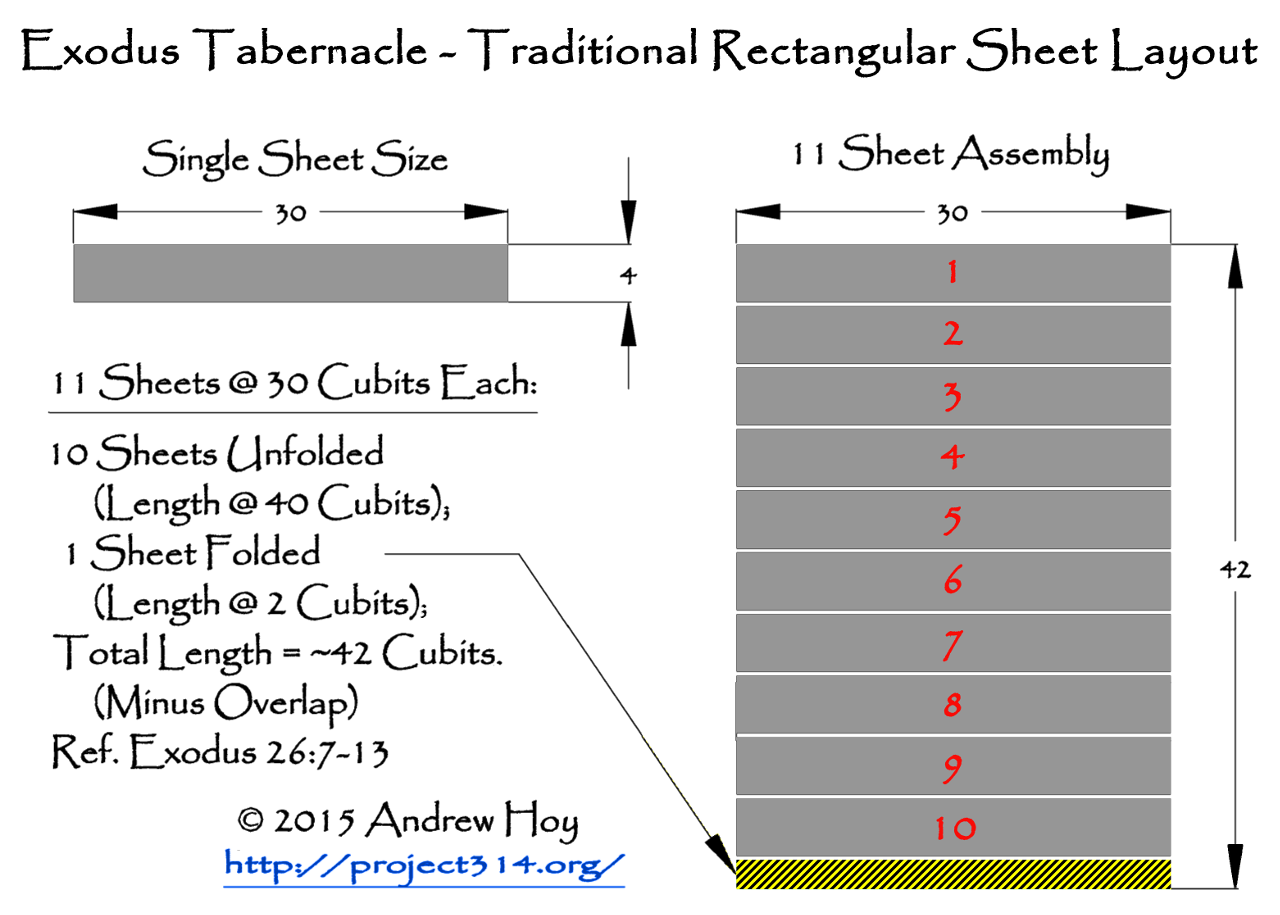

Although scholars have come to universally assume and fully accept the same top-to-bottom (i.e., long edge-to-long edge) curtain joining approach as depicted above, there is another simple—and more practical—approach to

joining eleven sheets together. In following the Exodus texts literally, the Tabernacle builders were to join the eleven like-for-like sheets via the "end edges" lengthwise (i.e., short edge-to-short edge),

thus creating an extremely narrow strip. Of course, at only 4 cubits wide but 330 cubits in length, the narrow strip would hardly function as a practical roof for “covering” a tent. However, joining all sheets at both edges (see the image below) would ultimately

yield a cylindrical assembly, appropriate for "covering" over a building's sides (just as described in Exodus 27:13), where the "covering" functions not as a roof, but as a barrier wall instead!

Of perhaps

equal or greater significance, the combined sheet dimensions and quantities point to a cylindrical sheet assembly. If joined together in a cylindrical arrangement, the sum of the eleven sheets measuring 30 cubits length,

minus the end sheet overlap (folded over per Exodus 26:12), and minus the nominal one cubit overlap adjustment (as each curtain end must slightly overlap with the adjacent one per Exodus 26:13), would be expressed as ([30 x 11] - [30 / 2] - 1), or (330-15-1), as is graphically depicted below.

Consequentially, when all of the proper edges are connected, the final length (i.e., the circumference) of the cylindrical sheet assembly amounts to 314 cubits, which is a near perfect multiple of the mathematical constant known as Pi or π.

To summarize,

the very same eleven fabric curtains that are assembled to make a single high aspect ratio 30 x 42 rectangular swatch or panel (joined via most of the long edges), as shown in the illustration above, would also create

a low aspect strip of curtains that formed a cylindrical assembly (joined via all short edges) measuring approximately 314 x 4 cubits, as shown below.

In later Exodus 27 texts, these same sheets are hung from metal frames in order to create Tabernacle courtyard walls. Not surprisingly, the dimensions for the courtyard are described as being exactly 100 cubits long (i.e.,

diameter), with the north and south portions each measuring 50 cubits “wide” (i.e., radius).

Given that a sheet has two sets of two parallel and opposing edges, the Exodus Tabernacle text leaves the reader with pairs of possibilities. In the image below, two options are presented for joining a set of sheets together (i.e., long edge vs short edge joints). Two types of shapes are credible for the final sheet assembly, depending upon end sheet connections or lack thereof (i.e., long flat plane vs short cylinder). Two final applications for the sheet assembly are viable (i.e., roof or wall).

As illustrated above, sheet orientation assumptions can drastically alter the presumed application of the sheets and thus have an impact on the perceived design of the balance of the Exodus Tabernacle.

When I first saw that the total start-to-end length of the sheet assembly was 314 cubits, something in my head instantly clicked. Right then and there, I knew I had discovered something magnificent, even though at the time I hadn’t a clue as to how the remainder of the dwelling place was arranged. Regardless, it was clear that the set of eleven wool curtains were arranged somewhat like a snow fence around the Tabernacle, the outer courtyard was clearly specified to be nothing less than a perfect circle! This number—a product of PI, i.e., π x 100—I came to think of as the "Rosetta Stone" for Moses' Tabernacle plans. It was this discovery that led me to question every other popular interpretation and scholarly assumption about the rest of the rectangular Exodus Tabernacle—including all of its other pieces. After all, it is bad engineering practice to try to force a proverbial "square peg" into a "round hole"—yet that is exactly what theologians do when they give preference to their preconceived notions while translating the Hebrew. For this reason, because this 314 key has somehow been lost during Israel’s exile, not a single English Bible translation in print makes any sense; and readers are consequentially misled, or forced to defer to the Hebrew for accurate descriptions, answers, and explanations.

With no doubt, the rediscovery of this "314 key" will forever change Bible interpretation—radically transforming how future scholars understand the Tabernacle texts—and many texts to follow. Clearly, it is not by accident that there is more Hebrew text describing the Tabernacle tent fabric than there is describing the Ark of the Covenant! As the Hebrew Exodus indicates, the Tabernacle sheets are a "thoughtful work". Why? The tent curtains weren't made first and foremost for decorative purposes. They were not “artistic work” made as fancy decor or for advancing esoteric mystical teachings; the sheets are as practical as they are a sign of intelligence. Surely, in this regard, fabrics used for the Tabernacle should be categorized as "engineered hardware", as opposed to a superfluous Bible detail that is not to be given any time or attention. Ironically, this great secret to the Tabernacle design was never ever meant to be covered; rather, the Tabernacle's secret is the covering... hidden in plain sight!

In conclusion, as the ancient Tent of Meeting is examined further, it becomes clear that God’s dwelling place was not invented out of necessity by Israel’s displaced masses after the Egyptian Exodus. Neither was the Tabernacle a creative endeavor of Moses, or the product of the desire of Moses’ assistant Betzalel. To the contrary, the Tabernacle invention came about by means of divine revelation. Revelation is the father of invention, and only God is the Father of revelation.