Finally, it is important to note that apart from attaining an "expert" status by means of academic credential or professional certification, many "experts" exist in the absence of a righteous moral standard. For example,

hitmen and loan sharks qualify as "experts" according to the general English definition; and needless to say, they should scarcely be applauded for practicing their crafts. Lest it be forgotten, Adolph Hitler

was generally seen by millions as an "expert" in his day in the profession of government, thereby leading an entire nation in all economic, eugenic, religious, and foreign affairs. Granted, this is not to say that all

leaders—who are approximated to be "experts"—hope to forward the same values and agendas as did Hitler, but this is to show an obvious example whereby people often have difficulty differentiating between charismatic

appeal and legitimate knowledge-based authority and expertise. Thus, masses of ignorant, apathetic, and morally confused people—such as those shown in the famous Nazi Hamburg shipyard photograph—leave

themselves completely ill-equipped to identify a true "expert", yet are able to do so within environments whereby the "majority rules" principle is used to define the moral good.

Today, objective

scholars—even German historians—are unlikely to see Hitler as an expert in governance, but rather as an expert in crowd psychology and emotional manipulation. While it is unlikely that every person saluting in

the Hamburg photograph actually believed that Hitler was truly an expert leader, history clearly shows the great danger in showing unconditional support, casual cooperation, or even passive consent to the status quo.

In hindsight, history seems to show that the single individual that is shown to be abstaining from the salute without apology (believed to be August Landmesser or Gustav Wegert) was the only political "expert" in the

crowd that day, whereas the remainder would come to bear some portion of the guilt for the death of millions as their cooperation and/or submission empowered a genocidal madman. This leaves simple questions

for the reader: Who do you salute as an "expert", and would you prefer to have your experts defined by popular opinion or peer pressure? Would you be more likely to stand beside a lone man speaking out in

a crowd, or would you stand behind a man simply because everyone else is calling him an "expert" or "der Führer"?

May this Hamburg photograph be a reminder of the dangers of misappropriated endorsement,

the lack of virtue in peer pressure, the potential for great wisdom among a dissenting minority, and the great public responsibility in influencing those perceived by the masses to be experts.

While the "expert" dictionary definition does little to expound upon the means by which one might be formally acknowledged as an "expert", it does even less to challenge the validity of such an idea or mental construct

altogether—which seems to be of questionable prudence.

About fifteen years ago, an Eastern Indian work colleague made a lasting impression as he shared a simple proverb with me. He explained

that "an expert is someone who knows almost everything about practically nothing". While self-proclaimed and credentialed experts alike might take offense at this ironic maxim, it makes a valid point about

the inherent limitations of lopsided knowledge acquisition. Coincidentally, English versions of the Hebrew Bible never or scarcely use the word "expert" in interpretation, which further suggests that using

titles such as "expert" is inappropriate and perhaps even idolatrous.

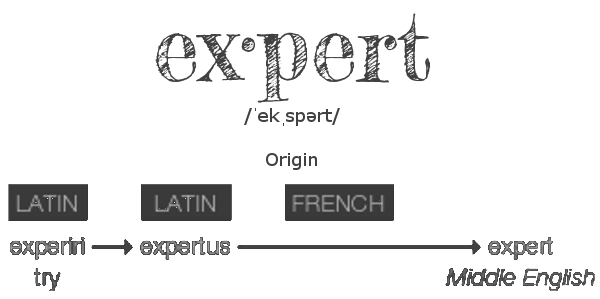

In reconsidering the reverence attributed to "expert" titles and personalities in today's society, it might be fitting to reflect upon the etymology of "expert", which is of Latin origin. "Expert", like "expertise"

and "experience", comes from the Latin root experiri, which simply means "to try". Curiously, the English noun "try" comes from a word meaning "a screen for sifting", which seems to be related

to a "tray" that might be used for sifting gold, which is ultimately associated with "an effort" or "an attempt"—as opposed to something producing results that are absolutely certain.

A Hebrew

Proverb seems to compare the quest for knowledge of God's word to panning for gold, as it is roughly translated into English, "Receive my instruction, and not silver; and knowledge rather than choice gold."

(Proverbs 8:10, KJV)

Understanding that prospectors need to roll up their sleeves, get wet and dirty, and process a volume of common soil and stone as they seek for treasures of greater weight, it is

fitting that the Scriptures might liken the pursuit of knowledge to this arduous process. While there is no guarantee that you will be instantly reward with huge nuggets of gold on your first attempt,

one thing is almost certain—you won't get gold or knowledge unless you try. In this regard, it is better to try and make an effort than it is to claim "expert" status, as a mere claim alone is not assured

to make anyone prosperous. Remember, if you try panning for gold next to an expert, you just might surprise yourself by how well you do.

Do you feel intellectually or academically inferior to someone that you have regarded to be an "expert", such as a pastor, rabbi, priest, minister, professor, teacher, or other religious authority? Is it possible

that your perception of their "expert" status is rooted in your own ignorance or insecurity—or is it because they have intimidated you with their credentials, or hopefully left you inspired at some point with their

knowledge or insight? Whatever the case, it is worth considering that it is possible that you may possess some knowledge that they lack—especially if it is pertaining to God's dwelling place, as revealed through

the plans of the Exodus Tabernacle. It has been my observation that the number of religious professionals having an intimate knowledge of the structure or the texts describing it are few and far between, and the

knowledge that most religious professionals have is rooted more in translation and in tradition than it is in the original Exodus texts themselves. In fact, it is likely that in studying and absorbing The House of El Shaddai materials

that you will be more knowledgeable in the subject matter than most any religious professional that might otherwise command your respect; and this knowledge should equip you to help the religious expert—as well as those

following their lead.

In order to help create true "experts", The House of El Shaddai—Questioning the Tabernacle Workbook was created. Of course, the simple act of completing a workbook by no means guarantees anyone to be an "expert" according to the modern "expert" connotation, but it does allow a person to become experienced and more intimately familiar with the subject matter. In other words, it gives people an opportunity to test or "try" their comprehension, that is to say to prove their knowledge to be true. This is the true essence of being an "expert", and in the case of the Questioning the Tabernacle workbook, it gives the student over 200 practical questions and intellectual exercises to do so.